Knee

- LCL Injuries

- LCL Injuries Non-Surgical Treatment

- LCL Injuries Surgical Treatment

- Recovering from LCL Surgery

- Patient Resources

LCL Injuries

What is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL)?

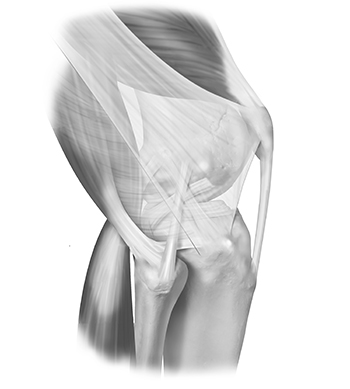

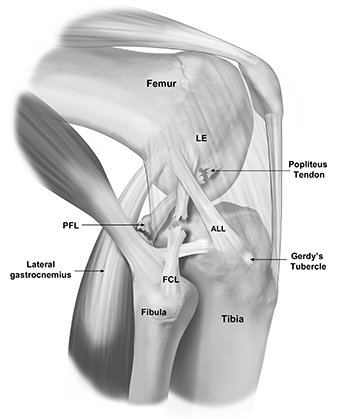

The lateral (fibular) collateral ligament (LCL or FCL) is a structure that stabilizes the lateral (outside) side of the knee connecting the thigh bone to the fibula (smaller of the two lower leg bones that sits on the outside). It prevents forces applied to the inner side of the knee from gapping open on the outside (varus stress).

The posterolateral corner of the knee, once known as “the dark side of the knee” because doctors did not have a clear understanding of the anatomy and biomechanics, is now a well-recognized cause of knee disability and dysfunction. There are three primary structures that comprise the posterolateral corner of the knee: the LCL, the popliteus tendon, and the popliteofibular ligament. All these structures work together to stabilize the outside of the knee. The LCL is like a tight rope that prevents your knee from gapping open on the outside of the knee. The popliteus tendon and the popliteofibular ligament prevent the tibia (shinbone) from externally rotating (outwards) on the femur (thigh bone).

What causes LCL injuries?

PLC injuries can occur in several ways including contact (i.e. hit/blow to the inside of your leg, car accident, pivoting injury) or noncontact injuries (falling on a hyperextended knee). These injuries allow the outside of the knee to gap open (varus gapping), as well as the increased external (outside) rotation of the lower leg (tibia).

Sometimes, the nerve that is very close to all these structures (the common peroneal nerve) can be affected. This is a highly debilitating injury that needs to be assessed as soon as possible by an experienced surgeon. This injury can sometimes lead to a foot drop (you cannot lift your foot/toes up towards the ceiling) because the nerve is damaged. Sometimes, the nerve can be decompressed restoring full function. Sometimes it is permanently damaged, and a tendon transfer (transferring a tendon from another part of the knee) can be done to help with the foot drop in order to make walking easier.

What are the symptoms of an LCL injury?

- Pain: Pain on the outer side of the knee is a common symptom of a torn LCL. The pain may range from mild to severe, depending on the extent of the injury.

- Swelling

- Stiffness: The knee may become stiff, making it difficult to fully bend or straighten the leg.

- Instability: An individual with a torn LCL may feel that the knee is unstable, as if it’s “giving way” or unable to support their weight properly, especially when shifting side-to-side.

- Movement: Difficulty stopping and cutting towards the affected side.

- Bruising: Bruising can develop around the site of the LCL tear, and the discoloration is often seen on the outer side of the knee.

- Difficulty Walking: Walking may be uncomfortable or painful, particularly if the LCL tear is severe or involving the entire PLC.

- Popping or Clicking Sensation: Some people report a popping or clicking sensation when the injury occurs, which may be followed by pain and swelling.

How is an LCL injury diagnosed?

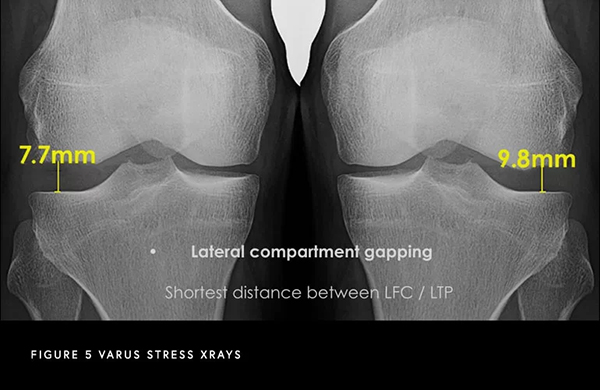

A combination of a comprehensive physical examination, special x-rays, and an MRI are usually very accurate. Dr. Bryan Penalosa and his team will perform a physical exam that will include testing your knee in an extended (straight) and flexed position to determine the location and severity of the injury. A special x-ray, called a varus stress x-ray, will likely be obtained. This special x-ray allows Dr. Penalosa to objectively quantify and diagnose (based on validated systems) a posteromedial corner injury with millimeter accuracy. An MRI will allow Dr. Penalosa to further evaluate the extent of the LCL injury as well as to evaluate the knee for any concomitant ligament, meniscal, or cartilage injuries.

LCL Injuries Non-Surgical Treatment

Can an LCL injury be treated without surgery?

Most injuries to the posterolateral corner (PLC) of the knee do not heal on their own. This is because the thighbone and shinbone (lateral femoral condyle of the femur and lateral tibial plateau of the tibia) are both convex (rounded), making this part of the knee inherently unstable when the ligaments and tendons are damaged. For this reason, PLC injuries should be evaluated and treated promptly to achieve the best outcomes.

Additionally, nearly all complete PLC injuries occur alongside injuries to other knee ligaments. When multiple ligaments are involved, surgical reconstruction is usually required to restore the normal anatomy and stability of the knee.

In some cases, a patient may suffer from an isolated LCL (lateral collateral ligament) injury. Depending on the severity, it may be possible to treat the injury non-surgically. Non-operative treatment includes:

Modifying activities to avoid movements that cause knee pain, instability, or excessive varus stress

Using over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications to reduce pain and swelling

Wearing a hinged knee brace for added support

Participating in physical therapy to strengthen surrounding muscles and restore stability

Typically, symptoms improve within 2–4 months of conservative treatment. If knee pain resolves and you can return to your desired level of activity, surgery is not needed for an isolated LCL injury.

LCL Injuries Surgical Treatment

What are the surgical options for an LCL or PLC injury?

Dr. Bryan Penalosa helped establish a global consensus on the treatment of posterolateral corner (PLC) injuries. Surgeons worldwide agreed that Grade 1 and 2 tears can often be managed nonoperatively with physical therapy, while Grade 3 tears almost always require surgical intervention.

When there is a complete tear of the LCL or injury to all structures of the PLC, surgery should ideally be performed within the first two weeks after injury, once range of motion has been restored. Treating the injury early allows the surgeon to repair the structures before significant scar formation occurs or the tissues weaken. It also allows the knee to be aligned anatomically, rather than healing in an abnormal position.

Modern reconstruction techniques have allowed many patients to return to high-level activities, which was not always possible in the past. Previously, a PLC injury could limit sports participation or even normal daily activities due to ongoing knee instability.

By restoring the native anatomy of the LCL and the posterolateral corner, patients can achieve early postoperative range of motion and better long-term outcomes. Using grafts, Dr. Bryan Penalosa performs a reconstruction technique that restores all the native insertions of the PLC ligaments. These grafts are typically allografts (from a donor) and are secured using non-metal screws.

In some cases, if treatment is delayed six weeks or longer, and the patient is slightly bow-legged (as is common in many men), a corrective osteotomy may be needed before the ligament reconstruction. This ensures that the newly reconstructed ligaments are not stretched out due to persistent varus stress on the knee.

Recovering from LCL Surgery

How long is the recovery after LCL surgery?

Depending on the severity of the LCL injury and the associated ligaments injured, recovery following LCL surgery can take between 6 and 12 months. Physical therapy starts on postoperative day 1 or 2 to work on range of motion. Patients should not bear weight on the operative side for the first six weeks after surgery. Driving on the operative knee is usually allowed at about seven to eight weeks postoperatively. Endurance and strengthening can be started in the second phase of the rehabilitation. Agility exercises start at 4 months post-op, along with the running progression if previous stages have been successfully achieved. Return to sport following an LCL surgery is typically at 9 months post-op.

Patient Resources

Orthopedic surgeon Dr. Bryan Penalosa and his team are dedicated to providing an industry-leading patient experience—one that is smooth, efficient, and convenient. Our team has compiled a comprehensive set of orthopedic patient resources to assist you with insurance information, patient forms, and much more.

Explore the patient resources below to learn more.

- Preparing for Surgery

- Traveling for Surgery

- Pre-Operative Clearance

- Peri-Operative Nutrition

- Post-Operative Instructions

- Post-Operative Physical Therapy

- Post-Operative Medications

- Durable Medical Equipment

- Billing & Insurance

- Patient Portal

- Medical Records

- Patient IQ

- Clinical Case and Imaging Review

- Ongoing Clinical Trials

- Sports Performance Center